Around a month ago, a 72-inch sewer line failed along Clara Barton Parkway in Montgomery County, Md. The Potomac Interceptor, owned and operated by DC Water, ruptured on Jan. 19, sending untreated wastewater into the C&O Canal and the Potomac River; what began as a local emergency has grown into one of the largest municipal wastewater spills in American history.

Related: Sewage Flows Toward Washington As Accountability Flows Away

Spill volume reaches historic levels

According to DC Water leaders' estimates, at least 243 million gallons of untreated sewage escaped during the first days after the collapse, while independent river advocates believe the total could approach 300 million gallons.

Either figure puts this incident among the largest wastewater disasters ever recorded in the United States, rivaling the 2017 Tijuana River spill along the California border, which released about 230 million gallons.

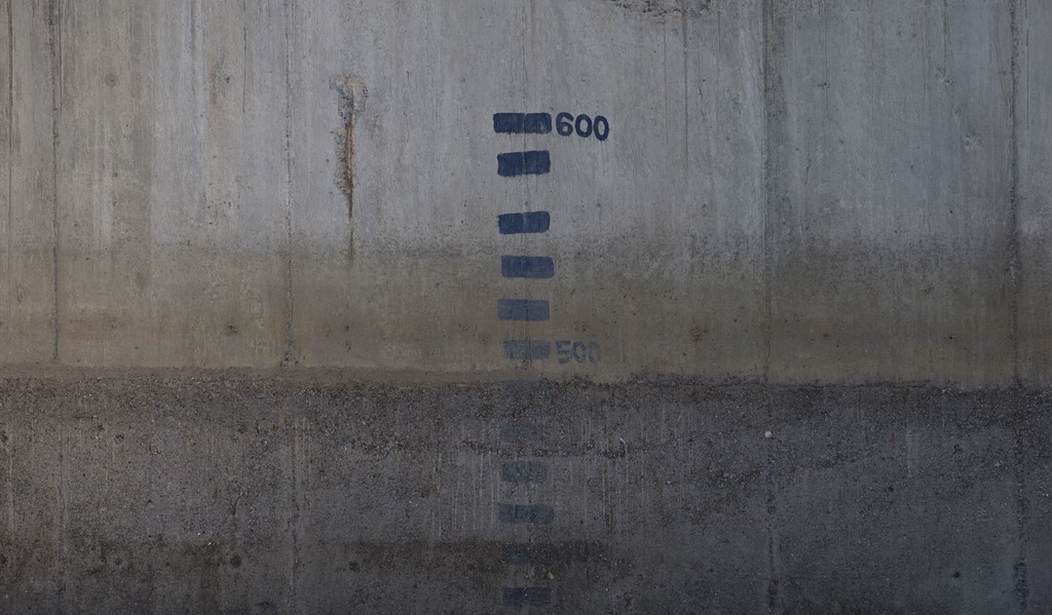

The Potomac Interceptor usually carries around 60 million gallons per day, and when the concrete wall failed, the river absorbed days of raw discharge before pumping began.

There's no serious dispute about the scale; the scene speaks for itself.

Aging pipe and buried rock block repairs

On a personal level, time is the most dangerous we meatsacks face, and it was the culprit here. Engineers traced the failure to the line's age and structural deterioration: The interceptor was installed during the 1960s.

Plans were in place to rehabilitate the facilities in September 2025, when DC Water launched the $625 phased effort. Unfortunately, the collapse struck first. COO and Executive Vice President of DC Water, Matt Brown, confirmed that construction backfill rock from the original dig shifted into the broken section, forming a dam about 30 feet downstream. Camera inspections on Feb. 5 confirmed that the obstruction was too far for vacuum trucks or jetting equipment to reach.

Now comes a stinky job: crews need to manually remove large boulders using slings and heavy equipment while stabilizing the surrounding soil. The project requires reinforcing the land surrounding the interceptor, so the extremely heavy equipment has a solid foundation to work from.

Bypass system expands, but risk remains

The first bypass pumps were activated on January 23. As of mid-February, four high-capacity pumps operate at a combined 114 million gallons per day, while three more pumps arrived from Florida and Texas. Crews finished two upstream access pits to support the growing system, essentially providing holding tanks.

CEO and GM of DC Water, David Gadis, pledged to expand environmental restoration once structural repairs are complete. However, until the bulkhead seals the section, giving crews a chance to remove the big rocks, hopefully preventing overflows during heavy rains.

Environmental damage continues

Bacteria levels near the collapse site remain dangerously elevated. Testing shows E. coli concentrations thousands of times higher than the safe swimming threshold of 410 colonies per 100 milliliters.

As I shared in January, it's a real danger for everybody.

Raw sewage plays host to E. coli, viruses, and chemical contaminants in waterways used for fishing, swimming, boating, and water intake. Advisories reduce risks but don’t prevent exposure, especially for communities without access to timely alerts.

The same demographic of people who always get hurt are at high risk here: children, the elderly, and the immunocompromised. Environmental harm extends well beyond immediate health effects, as aquatic life suffers long-term consequences that rarely make headlines.

Enforcement of the environmental factors typically focuses on private actors while giving public utilities a pass, but the river doesn’t care whose fault it is.

In addition to what we can't see, there are plenty of other things we wish we couldn't: wipes that aren't biodegradable, women's sanitary products, and more litter the banks downstream of the spill.

Health officials in Virginia and Maryland maintain advisories urging residents and pet owners to avoid direct contact with river water until testing stabilizes.

Repair timeline stretches into late 2026

Matt Brown told Maryland lawmakers that stopping the overflow conditions may take another four to six weeks, while permanent sliplining and structural reinforcement might need nine more months, creating a completion date towards the end of 2026.

My January column warned that sewage was flowing toward Washington, while accountability was flowing away. Weeks later, pumps hum around the clock, while heavy machinery stands ready, and crews work in freezing mud — and other material. However, the river still carries the heaviest burden.

It's rare for large infrastructure failures to erupt after warning signs. The concrete poured during the Cold War era now requires repairs beyond simple patchwork.

The Potomac wastewater crisis ranks among the worst in modern American history. Recovery will take time.

But vigilance takes longer.

Serious investigative reporting requires support. Join PJ Media VIP for deeper analysis, exclusive content, and ongoing updates on stories that affect infrastructure, public health, and accountability.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member