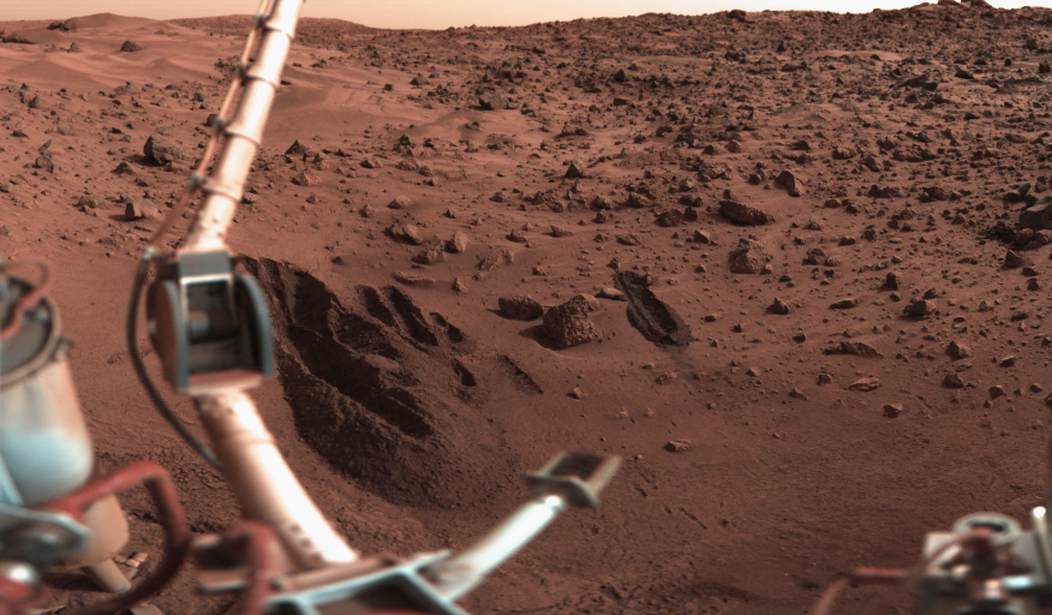

On July 20, 1976, one of the two Viking spacecraft sent to Mars landed and took spectacular, high-resolution photos of the Red Planet's surface for the first time. Viking 2 landed on September 3. Together the science performed by those two spacecraft revolutionized our understanding of Mars.

The Vikings' primary mission was to provide a definitive answer to whether there was life as we know it on Mars.

The results were originally inconclusive, despite at least two tests meeting mission criteria for the presence of microbes on Mars. The Labeled Release experiment was especially compelling.

The landers were equipped with a movable arm that could scoop up a soil sample and place it in a compartment that was a mini-bio lab.

A soil sample was "fed" a drop of nutrient solution containing radioactive carbon-14. If microbes were present, they would "eat" the nutrients and exhale radioactive carbon dioxide (CO2). Both landers (Viking 1 and 2) detected a massive, immediate spike of radioactive gas.

When the soil was heated to 320 degrees F to "sterilize" it, the reaction stopped completely—exactly what you would expect if life had been killed.

Despite these results, NASA eventually concluded that the reaction was likely caused by non-biological "oxidants" (such as perchlorates) in the soil.

In fact, two other experiments also provided indications that could have resulted from a biological process. They were also shot down when possible, non-biological alternatives were advanced. NASA wanted to be absolutely 100% sure before making the shattering announcement that life elsewhere in the universe had been scientifically proved, and decided to wait for undeniable, definitive proof.

The Viking landers apparently never provided it, even after years of analysis and scientific debate. It's a debate that's still ongoing today as the evidence is re-examined with 21st-century tools.

In reviewing an experiment that used a Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS) to detect organic molecules necessary for life, scientists led by Steve Benner, a professor of chemistry at the Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution in Florida, say the interpretation of the data was incorrect.

"The GC-MS showed an absence of organic molecules, or at least that was the [Viking team's] interpretation," Benner told Space.com. "The problem is that we now know that it did find organic molecules!"

The GC-MS worked by heating samples of Martian dirt — first to 120 degrees Celsius (248 degrees Fahrenheit) to remove any excess carbon dioxide from Mars' atmosphere, and then to 630 degrees C (1,166 degrees F) in order to vaporize any organics present in the dirt so that they could be analyzed by the mass spectrometer.

The goal was to boil away atmospheric contamination and then vaporize living organisms to determine if they emitted a waste product, as all living organisms on Earth do.

Puzzlingly, all that the mass spectrometer detected was an unexpected second burst of carbon dioxide and a small quantity of methyl chloride and methylene chloride, when instead there should have been some organic molecules present, if only from meteoritic debris that had built up over billions of years. For there to be none at all, argued the Viking team, required an unknown oxidant. Meanwhile, the carbon dioxide was assumed to have been left over from being observed by the container holding the sample, while methyl chloride was thought to be terrestrial contamination from cleaning solvents originating from the clean room on Earth where the instrument was assembled. This conclusion was bolstered by the fact that, during in-flight tests on the way to Mars, freons such as chlorofluorocarbons that had come from the clean room had been detected.

The Viking team at the time concluded an "oxidant" was responsible for the false positives, probably carried to Mars as a residual chemical from the "Clean Room" where the landers were kept to prevent earthly microbes from hitching a ride on spacecraft. Benner disagrees.

"In 2010, Rafael Navarro-González [a NASA astrobiologist who worked on the Curiosity rover mission] showed that organics plus perchlorate produces methyl chloride and carbon dioxide," said Benner.

Benner adds, "So now we know that the GC-MS didn't fail to discover organics — it did discover them, through their degradation products." If Benner's hypothesis is correct, all three experiments on Viking found evidence of biological life.

Overturning scientific conclusions set in stone, such as the notion that the Viking Landers found no evidence of life, will be difficult.

Benner thinks that the initial misinterpretation of the GC-MS results has set astrobiological research on Mars back 50 years. Instead of a healthy debate about the merits of the Viking evidence for life on Mars, discussion was shut down and the official line ever since, repeated in textbooks, is that the Viking missions found no evidence for life.

To make up for lost time, Benner is now calling for that back-and-forth debate — the very nature of the scientific method — to begin in earnest now, the 50th anniversary year of the Viking 1 and 2 Mars landings.

Is Benner's theory compelling enough to reopen a question settled almost 50 years ago? It's happened before. Scientists believed for thousands of years that gravity was a "force." Einstein proved it to be the curvature of spacetime.

For nearly 2,000 years, the Western world believed that the Earth was the stationary center of the universe. Galileo’s telescope observations of Jupiter's moons proved that not everything orbited Earth, and Johannes Kepler showed that orbits were elliptical rather than circular.

Overthrowing scientific consensus is part of the scientific process. It's a never-ending quest for facts that some scientists seem to have forgotten when it comes to some issues, like climate change. A real scientist questions everything and keeps an open mind when it comes to ideas that might contradict long-held beliefs.

We may answer the question of life on Mars definitively in the next decade, as SpaceX and Rocket Lab's Mars sample-return missions will collect soil and rock samples and return them to an orbiting lab.