It looks like something from a movie set about a futuristic world, or maybe the old cartoon The Jetsons.

Built into a hillside and shaped like a three-sided pyramid, it sits on about 25 acres and is seven levels high, not including the geodesic dome on top. It was once meant to house over 300 boutiques, numerous cinemas, a park, a fancy hotel and club, and a heliport, among other things. Two miles of driveway spiral around it, allowing cars to drive all the way to the top. You can supposedly see it from almost any point in the Caracas Valley.

Some call it the most interesting and unique piece of architecture in Latin America. But many others call it hell on Earth.

I'm talking about El Helicoide.

El Helicoide de Caracas es un resumen construido de la historia de Venezuela.

— Pedro Torrijos (@Pedro_Torrijos) January 9, 2026

Un centro comercial nacido para un futuro motorizado y voraz, que se recorrería en coche —sin bajarse de él— pero acabó convertido en prisión.

Os cuento su historia en #LaBrasaTorrijos 🧵⤵️ pic.twitter.com/rk4gKGrWGg

It was the concept of the Venezuelan dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez, who began the project in the 1950s. He saw this grand shopping mall as a way to show the world how well the country was doing as its oil industry boomed. Many families were displaced, their homes torn down so that it could become an iconic location where everyone wanted to be in Caracas.

He was eventually overthrown, and by 1961, about a year short of completion, construction stopped. Despite many attempts to revive it, including one from Nelson Rockefeller, who tried to buy it during the 1970s, the architectural marvel sat empty for years. Officially, anyway — but during the 1970s and early 1980s, it became home to thousands of squatters.

Eventually, the Venezuelan government began using portions of it to house government offices, specifically its intelligence agency. But in 2014, Nicolás Maduro found a new use for it: locking up and torturing political prisoners. Maduro took over the country when Hugo Chávez died in 2013, but he was never very popular. Around this time, the opposition was becoming stronger, the economy was tanking, and people began to rise up and protest and march in the streets.

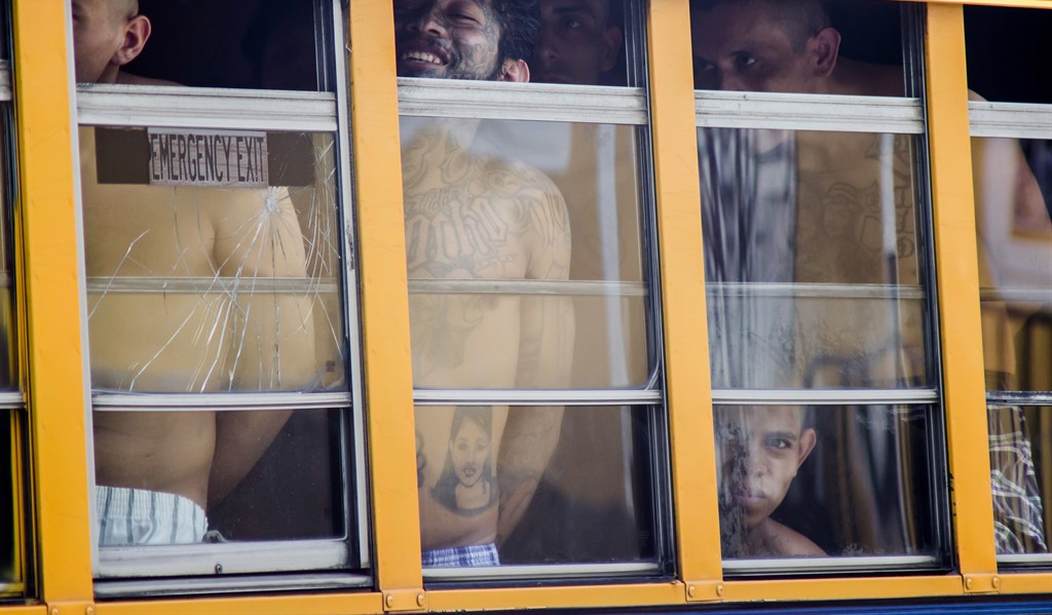

According to guards who once worked at El Helicoide, the government began busing protesters in, dozens at a time, and stuffing them inside the cells at the makeshift prison. Authorities had given the order that any gathering of four or more people in the streets was considered illegal, and those people were to be arrested. The numbers grew so large that the guards began turning offices and stairwells into jail cells.

The "prisoners" were crammed into small cells, often with no light, no fresh air, no toilet, or nothing to sleep on but a sheet on the floor. They used the bathroom in water bottles and plastic bags and would go weeks without any type of shower or hygiene. The rooms were hot and humid, and food and excrement were left inside to rot.

There was no legal process, no looming court dates. Guards were told to pressure the political prisoners into confessing to crimes they did not commit. They'd do this through physical and mental torture. Suffocation with plastic bags. Electrocuting a person on their most sensitive body parts. Tying up a person's hands and feet and connecting the rope to a pulley. People would eventually lie just to avoid the pain.

The Maduro regime is also a big fan of white torture, and it would allegedly lock individual prisoners in cells that were about six by seven feet, with only a cement bed and a toilet for water. Bright lights shine on them 24/7, and the cells are kept freezing cold. There is no sound, no communication with the outside world — just day after day of losing your sense of time and identity.

Keep in mind that these are not real criminals — just people with their own political opinions. But they were often locked up with rapists and murderers.

Human rights organizations were sometimes allowed to visit, and despite finding numerous prisoners in poor health, they were threatened and intimidated into lying about their findings.

I watched a BBC documentary on El Helicoide, and one of the former guards interviewed told the story of a 64-year-old well-educated pilot who was arrested for giving money to the opposition party. He was always on his best behavior, only asking for the medicine he needed, but after months of psychological torture, he hung himself.

The documentary also focused on a former congressman and human rights activist, Rosmit Mantilla, who spent over two years in El Helicoide. "I went to sleep and woke up in fear," he said of his days there. He was often surrounded by people being raped and tortured. Eventually, his health began to deteriorate. After much controversy, he was finally released, largely thanks to international pressure. He now lives in exile in France and continues to advocate for the other political prisoners in Venezuela.

In 2018, the prisoners attempted to revolt against the guards, but a little tear gas and buckshot supposedly put an end to that.

In 2022, a United Nations fact-finding mission documented numerous cases of torture by the Venezuelan General Directorate of Military Counterintelligence (DCGIM) and the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN), which is run by Diosdado Cabello and still has its headquarters inside El Helicoide. The UN report found that guards "suffocate detainees with plastic bags, rape them with wooden sticks, and apply electric shocks to their genitals." The report also mentioned "gross violations of human rights, including extrajudicial executions, enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention, torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, including those involving sexual and gender-based violence, committed since 2014."

Despite this knowledge, El Helicoide still operates in the same way today. It sits between the parishes of San Pedro and San Agustín and sticks out like a sore thumb in the midst of several barrios. The building has become a symbol of the country itself.

As I'm writing this on Tuesday night, Jan. 13, 2026, dozens of families are gathered outside, holding a candlelight vigil for their loved ones who are likely inside.

For the sixth consecutive night, families of political prisoners are spending the night outside El Helicoide, waiting for the regime of Delcy Rodríguez to fulfill the promise made to President Trump and release all political prisoners.

— Emmanuel Rincón (@EmmaRincon) January 14, 2026

So far, they have been deceiving both the… pic.twitter.com/nNPoeh06CW

As I've been reporting, the president of the Venezuelan National Assembly, Jorge Rodríguez, promised last week that he would release a significant number of political prisoners, and Donald Trump followed that up with a confirmation that it would happen on Friday. Earlier today, Rodríguez announced that 400 of the 800 to 1,000 who are incarcerated had been released. That is simply not true. Organizations on the ground can only confirm 56, as I last checked, which is the same number I reported last night.

Opposition leader María Corina Machado met with the pope on Monday, and these prisoners were one of the main topics of conversation. She will meet with President Trump on Thursday and, no doubt, make a plea on their behalf. Last week, Trump said publicly that Venezuela would be closing a "torture chamber," and while he didn't name El Helicoide, that's most likely the place he was referring to. However, there have been no signs of that happening either.

It'll be interesting to see what happens. Even though not all of the political prisoners are held in El Helicoide, you can see why many of their loved ones fear they may never actually make it out in good health or even alive.