The Glyptodont was an extraordinary beast. It was a giant, armadillo-like creature that lived 50,000 years ago and grew to the size of a Volkswagen Beetle, weighing in at around two tons.

Many scientists believe that the Glyptodont, the Woolly Mammoth, Saber Tooth Cat, and other "megafauna" that existed for hundreds of thousands of years died off as a result of climate change that peaked about 25,000 years ago. That "Glacial Period" is cited as the reason we don't run into a Woolly Rhinoceros or a Short Face Kangaroo while out walking in the woods.

Now, more recent research points to a different culprit: us.

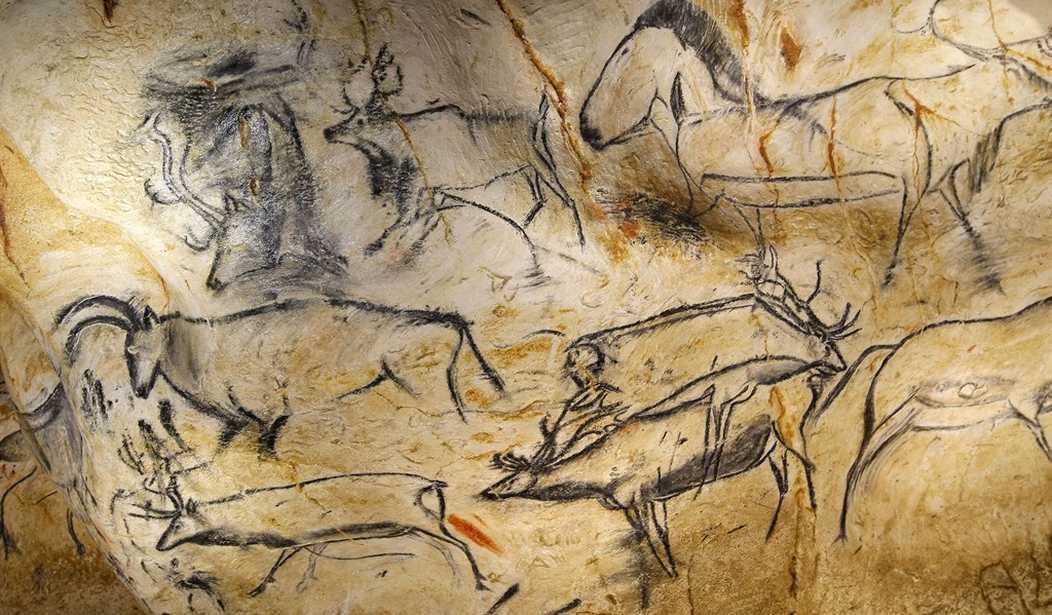

“We know that prehistoric humans were very focused on hunting big species,” says Jens-Christian Svenning, director of the Danish National Research Foundation’s Center for Ecological Dynamics in a Novel Biosphere at Aarhus University. Svenning is also the lead author of a recent paper titled "Extinction," published in Cambridge Prisms.

The "Killer Human" theory was first advanced in 1966 by an American paleontologist named Paul Schultz Martin. "He suggested that migrating humans hunted North American megafauna from the Pleistocene epoch to extinction," writes Summer Ryalander in Nautilus.

Svenning and his team analyzed ancient extinction, climate, and human migration data gathered over the last 60 years. They also relied on previous research, including a paper published in 2021 by Nature Communications that examined megafauna extinction in South America. That paper also noted the close alignment with human demographic data and the finding of spear points called fishtails in the archaeological record.

“We have a much better understanding now than in the 1960s,” Svenning says. “What we have done is reassessed all this data and it allows us to say that altogether, we can really rule out that climate has played a major role in this kind of extinction.”

The where’s and when’s of extinctions just don’t line up with global patterns of climate change, according to the data the researchers collected and analyzed, but they do correspond closely with patterns of human colonization—occurring at or after our arrival in many distinct times and places around the globe.

“We conclude that it’s one of the strongest, most consistent patterns we have in ecology,” says Svenning. His team’s findings indicate that these patterns of megafauna extinction began when humans first migrated out of Africa some 100,000 years ago. The extinctions accelerated approximately 50,000 years ago as Eurasia and Australia were colonized by large game-hunting humans.

Ending up on the business end of a spear had such a significant impact on large mammals because they have a naturally slow replacement rate. Gestation periods are long, and so is the process of maturation. The 46 species of megaherbivores that have been lost to history simply could not have reproduced fast enough to offset human kills.

Felisa Smith, a conservation paleoecologist at the University of New Mexico, thinks the case has been made for human hunting leading to mass megafauna extinction.

“I think work over the past few decades has rather convincingly demonstrated that humans had a pretty substantial part in the extinction,” says Smith.

Some observers try to make the case that humans should somehow be blamed for hunting these animals to extinction.

Say what?

Svenning thinks that's an idiotic criticism.

“People who lived thousands of years ago never had access to the full picture," said Svenning. "These things took place across long time scales and big spatial scales over which no one had an overview; whatever people did, it was difficult to see the consequences. Plus, of course, people just had to survive the best they could.”

Easter Island was one of the last places on Earth that humans colonized. Polynesians settled there around 1200 AD. By the time Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen arrived in 1722, he described the island as virtually treeless.